The Stuarts

- James I

In 1629 Charles I dismissed Parliament and forbade people to speak of calling another, this was the start of Personal Rule. In the body of this essay the events and disputes that led to this situation will be explored fully.

In 1629 Charles I dismissed Parliament and forbade people to speak of calling another, this was the start of Personal Rule. In the body of this essay the events and disputes that led to this situation will be explored fully.

The religious reform was led by William Laud, raised to the rank of archbishop of Canterbury in 1633. Laud looked for religious uniformity by dismissing the non-conformist clergy and closing puritanical organizations, so he violated the freedom of conscience of the free and common man. To punish those who refused to conform to the religious norms established by the Church of England they had the arbitrary courts of the kingdom, the Supreme Commission Court and the Chamber of the Starry Court.

The religious reform was led by William Laud, raised to the rank of archbishop of Canterbury in 1633. Laud looked for religious uniformity by dismissing the non-conformist clergy and closing puritanical organizations, so he violated the freedom of conscience of the free and common man. To punish those who refused to conform to the religious norms established by the Church of England they had the arbitrary courts of the kingdom, the Supreme Commission Court and the Chamber of the Starry Court.

Test act

Charles I

Relationship with Parliament

In 1629 Charles I dismissed Parliament and forbade people to speak of calling another, this was the start of Personal Rule. In the body of this essay the events and disputes that led to this situation will be explored fully.

In 1629 Charles I dismissed Parliament and forbade people to speak of calling another, this was the start of Personal Rule. In the body of this essay the events and disputes that led to this situation will be explored fully.

Charles himself was described as aloof and unyielding. He believed strongly in divine right, he saw any critcism as being potentially treacherous.

His communication skills were also poor, his aloof style meant his speeches to parliament were rebukes and he would allow no counter arguments. These factors of his personality had damaging effects in his relationship with the country at large.

During 1625-29 the gap between the political nation and the Kings court began to widen. Charles only took advise from his court.

Buckingham effectively controlled the court right up to his assassination. He dismissed any agitators from court and controlled the flow of patronage.

This had damaging effects on the political nation and their relationship with the King.

William Laud

The religious reform was led by William Laud, raised to the rank of archbishop of Canterbury in 1633. Laud looked for religious uniformity by dismissing the non-conformist clergy and closing puritanical organizations, so he violated the freedom of conscience of the free and common man. To punish those who refused to conform to the religious norms established by the Church of England they had the arbitrary courts of the kingdom, the Supreme Commission Court and the Chamber of the Starry Court.

The religious reform was led by William Laud, raised to the rank of archbishop of Canterbury in 1633. Laud looked for religious uniformity by dismissing the non-conformist clergy and closing puritanical organizations, so he violated the freedom of conscience of the free and common man. To punish those who refused to conform to the religious norms established by the Church of England they had the arbitrary courts of the kingdom, the Supreme Commission Court and the Chamber of the Starry Court.

THE REPUBLIC:

OLIVER CROMWELL

Oliver Cromwell was and English politician

and military. He was born in Huntingdon, England, in the 25th of April in 1599.

He turned England in a republic called Commonwealth of England.

During the first 40 years of his life he was

no more than a middle-class landowner, but he ascended incredibly until he

commanded the New Model Army and, in the long run, impose his leadership on

England , Scotland and Ireland as ‘Lord Protector’, from the December 16, 1653,

until the day of his death. Since then he has become a very controversial

figure in English history:

For some historians he was not more than a

regicidal dictator; for others he was a hero of the struggle for freedom.

His career is

full of contradictions. He was a regicide who questioned whether or not he

should accept the crown for himself and finally decided not to, but he

accumulated more power than Charles I of England.

Religious fanatic follower of protestant Christianity, its campaigns of

conquest of Ireland and of Scotland were brutal even for the canons of the

time, since it considered that it fought against herejes.

Under his

command, the Protectorate defended freedom of worship and conscience, but

allowed the blasphemers to be tortured, in addition to cruelly persecuting

Catholics. He was in favor of the criterion of equity in justice, but locked

those who criticized his policy of raising taxes without the permission of the

Parliament of England.

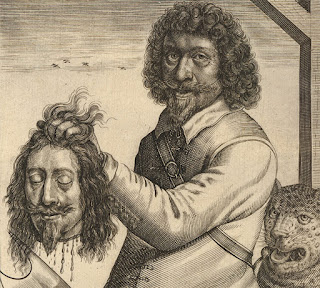

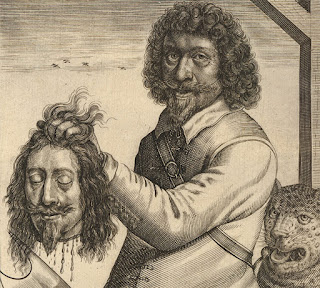

His admirers

cite him as a strong, stabilizing leader with a sense of state, who gained

international respect, overthrew tyranny and promoted the republic and freedom.

His critics consider him an openly ambitious hypocrite who betrayed the cause

of freedom, imposed a puritanical system of values, and showed scant respect

for the country's traditions. When the monarchists returned to power, his body

was unearthed, hung by chains and decapitated, and his head exposed for years

to public derision.

Commonwealth: The Rump Parliament.

After the

king's execution, a republic known as the Commonwealth of England was

established. A State Council was established to manage the country, which

included Cromwell among its members. His real power came from the army;

Cromwell tried unsuccessfully to unify the original group of "Royal

Independents" centered around St John, Saye and Sele, but only St John

agreed to hold on to his seat in Parliament. From the middle of 1649 to 1651,

while Cromwell was absent in campaign, with the deposed King (and next to him

the unifying factor of his cause), the different factions of the Parliament

began to be immersed in internal disputes.

Upon his return, Cromwell tried to influence the members of Parliament to establish the date of the next elections, uniting the three kingdoms under a single policy and setting in motion a tolerant national church. However, the Rump Parliament wavered in the election of date for the elections, and although it launched a basic freedom of conscience, it did not manage to elaborate an alternative to the religious taxes, nor was able to dismantle other aspects of the existing religious situation. Frustrated, Cromwell ended up dissolving Parliament in 1653.

Upon his return, Cromwell tried to influence the members of Parliament to establish the date of the next elections, uniting the three kingdoms under a single policy and setting in motion a tolerant national church. However, the Rump Parliament wavered in the election of date for the elections, and although it launched a basic freedom of conscience, it did not manage to elaborate an alternative to the religious taxes, nor was able to dismantle other aspects of the existing religious situation. Frustrated, Cromwell ended up dissolving Parliament in 1653.

‘Berebone Parliament’.

After the

dissolution of the Rump Parliament, the power temporarily happened to

a council that debated on the form that the constitution had to take.

Finally, the

assembly was commissioned to find a permanent constitutional and religious

agreement. Cromwell was invited to join, but declined the offer. However, the

failure of the assembly to achieve its objectives led its members to vote in

favor of its dissolution on December 12, 1653.

The Protectorate:

After the

dissolution of the Barebone Parliament, John Lambert promoted a new

constitution known as the Instrument of Government, very similar to the

previous Principal Proposals.

He turned Cromwell into Lord Protector for life to achieve "the highest office and the administration of the government." He had the power to call and dissolve parliaments, but he was obliged by the Instrument to seek the majority vote for the Council of State. However, the power of Cromwell was also reinforced by his great popularity in the army, which he had expanded during the civil wars, and which he prudently kept afterwards in good shape. Cromwell accepted the oath as Lord Protector on December 15, 1653.

He turned Cromwell into Lord Protector for life to achieve "the highest office and the administration of the government." He had the power to call and dissolve parliaments, but he was obliged by the Instrument to seek the majority vote for the Council of State. However, the power of Cromwell was also reinforced by his great popularity in the army, which he had expanded during the civil wars, and which he prudently kept afterwards in good shape. Cromwell accepted the oath as Lord Protector on December 15, 1653.

Cromwell died finally in 1658, and his son

Richard was his successor as Lord Protector. Although he was not completely exempt from

skill, Richard had no support in either Parliament or the army, and was forced

to resign in the spring of 1659, bringing the Protectorate to an end. In the

period immediately after his abdication, the head of the army, George Monck,

took power for less than a year, at which time Parliament reinstated Charles II

of England as king.

CHARLES II

OF ENGLAND

Charles II (29 May 1630– 6 February 1685) was king of England,

Scotland and Ireland. He

was king of Scotland from 1649 until his deposition in 1651, and king of

England, Scotland and Ireland from the restoration of the monarchy in 1660

until his death.

Charles II's father, Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the

climax of the English Civil War. Although the Parliament of Scotland proclaimed Charles II

king on 5 February 1649, England entered the period known as the English

Interregnumor the English

Commonwealth, and the country was a

de facto republic, led by Oliver Cromwell. Cromwell defeated Charles II at the battle of Worcester on

3 September 1651, and Charles fled to mainland

Europe. Cromwell became virtual dictator

of England, Scotland and Ireland, and Charles spent the next nine years in

exile in France, the Dutch Republic and the Spanish

Netherlands.

A political crisis that followed the death of Cromwell in 1658 resulted in the restoration of the monarchy, and Charles was invited to return to Britain. On 29 May 1660, his 30th birthday, he was received in London to public acclaim. After 1660, all legal documents were dated as if he had succeeded his father as king in 1649.

A political crisis that followed the death of Cromwell in 1658 resulted in the restoration of the monarchy, and Charles was invited to return to Britain. On 29 May 1660, his 30th birthday, he was received in London to public acclaim. After 1660, all legal documents were dated as if he had succeeded his father as king in 1649.

The

Restoration

After the death of Cromwell in 1658, Charles's chances

of regaining the Crown at first seemed slim as Cromwell was succeeded as Lord

Protector by his son, Richard.

However, the new Lord Protector had little experience of either military or

civil administration. In 1659, the Rump Parliament was recalled and Richard

resigned. During the civil and military unrest that followed, George Monck, the

Governor of Scotland, was concerned that the nation would descend into

anarchy.Monck and his army marched into the City of London and forced the Rump

Parliament to re-admit members of the Long Parliament who had been excluded in

December 1648 during Pride's Purge. The

Long Parliament dissolved itself and for the first time in almost 20 years,

there was a general election. The outgoing Parliament defined the electoral

qualifications so as to ensure, as they thought, the return of a Presbyterian

majority.

The restrictions against royalist candidates and

voters were widely ignored, and the elections resulted in a House of Commons that

was fairly evenly divided on political grounds between Royalists and

Parliamentarians and on religious grounds between Anglicans and Presbyterians. The

new so-called Convention Parliament assembled on 25 April 1660, and soon

afterwards welcomed the Declaration of Breda, in

which Charles promised lenience and tolerance. There would be liberty of

conscience and Anglican church policy would not be harsh. He would not exile

past enemies nor confiscate their wealth. There would be pardons for nearly all

his opponents except the regicides. Above

all, Charles promised to rule in cooperation with Parliament.The English

Parliament resolved to proclaim Charles king and invite him to return, a

message that reached Charles at Breda on 8 May 1660. In Ireland, a convention had

been called earlier in the year, and had already declared for Charles. On 14

May, he was proclaimed king in Dublin.

The clarendon

code

The Convention Parliament was dissolved in December

1660, and, shortly after the coronation, the second English Parliament of the

reign assembled. Dubbed the Cavalier Parliament, it was overwhelmingly Royalist

and Anglican. It sought to discourage non-conformity to the Church of England,

and passed several acts to secure Anglican dominance.

The Corporation Act 1661 required municipal officeholders to swear allegiance; the Act of Uniformity 1662 made the use of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer compulsory; the Conventicle Act 1664 prohibited religious assemblies of more than five people, except under the auspices of the Church of England; and the Five Mile Act 1665 prohibited expelled non-conforming clergy men from coming within five miles (8km) of a parish from which they had been banished. The Conventicle and Five Mile Acts remained in effect for the remainder of Charles's reign.

The Acts became known as the "Clarendon Code", after Lord Clarendon, even though he was not directly responsible for them and even spoke against the Five Mile Act.

The Corporation Act 1661 required municipal officeholders to swear allegiance; the Act of Uniformity 1662 made the use of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer compulsory; the Conventicle Act 1664 prohibited religious assemblies of more than five people, except under the auspices of the Church of England; and the Five Mile Act 1665 prohibited expelled non-conforming clergy men from coming within five miles (8km) of a parish from which they had been banished. The Conventicle and Five Mile Acts remained in effect for the remainder of Charles's reign.

The Acts became known as the "Clarendon Code", after Lord Clarendon, even though he was not directly responsible for them and even spoke against the Five Mile Act.

The Restoration was accompanied by social change. Puritanism

lost its momentum. Theatres reopened after having been closed during the protectorship

of Oliver Cromwell, and bawdy "Restoration comedy" became a

recognisable genre. Theatre licences granted by Charles required that female

parts be played by "their natural performers", rather than by boys as

was often the practice before; and Restoration literature celebrated or reacted

to the restored court, which included libertines such as John Wilmot, 2nd Earl

of Rochester.

Test act

The Test Acts were a series of English penal laws that served as a religious test for public

office and imposed various civil disabilitieson

Roman Catholics and nonconformists. The principle was that none but

people taking communion in the established Church

of England were eligible for public employment, and the severe penalties

pronounced against recusants, whether

Catholic or nonconformist, were affirmations of this principle. In practice

nonconformists were often exempted from some of these laws through the regular

passage of Acts of Indemnity. After 1800

they were seldom enforced, except at Oxbridge,

where nonconformists and Catholics could not matriculate (Oxford) or graduate

(Cambridge).

This act was followed by the Test Act of 1673 (25 Car.

II. c. 2) (the long title of which is "An act for preventing dangers which

may happen from popish recusants"). This act enforced upon all persons

filling any office, civil or military, the obligation of taking the oaths of

supremacy and allegiance and subscribing to a declaration against transubstantiationand

also of receiving the sacrament within three months after admittance to office.

The oath for the Test Act of 1673 was:

I, N, do declare that I do believe that there is not

any transubstantiation in the sacrament of the Lord's Supper, or in the

elements of the bread and wine, at or after the consecration thereof by

any person whatsoever.

The act was passed in the parliamentary session that

began on 4 February 1673; the act is dated as 1672 in some accounts because the

Julian calendar then in force held that the new year did not begin until Lady

Day, or 25 March. The correct date using the modern Gregorian calendar is

1673.

POLITICAL PARTIES

Tories

The first Tory party could trace its principles and

politics, though not its organization, to the English Civil War which divided

England between the Royalist (or "Cavalier") supporters of King Charles

I and the supporters of the Long Parliament upon which the King had declared

war. This action resulted from this parliament not allowing him to levy taxes

without yielding to its terms. In the beginning of the Long Parliament (1641),

the King's supporters were few, and the Parliament pursued a course of reform

of previous abuses.

The increasing radicalism of the Parliamentary majority, however, estranged many reformers even in the Parliament itself and drove them to make common cause with the King. The King's party thus comprised a mixture of supporters of royal autocracy and of those Parliamentarians who felt that the Long Parliament had gone too far in attempting to gain executive power for itself and, more especially, in undermining the episcopalian government of the Church of England, which was felt to be a primary support of royal government.

By the end of the 1640s, the radical Parliamentary programme had become clear: reduction of the King to a powerless figurehead and replacement of Anglican episcopacy with a form of Presbyterianism.

The increasing radicalism of the Parliamentary majority, however, estranged many reformers even in the Parliament itself and drove them to make common cause with the King. The King's party thus comprised a mixture of supporters of royal autocracy and of those Parliamentarians who felt that the Long Parliament had gone too far in attempting to gain executive power for itself and, more especially, in undermining the episcopalian government of the Church of England, which was felt to be a primary support of royal government.

By the end of the 1640s, the radical Parliamentary programme had become clear: reduction of the King to a powerless figurehead and replacement of Anglican episcopacy with a form of Presbyterianism.

This prospective form of settlement was prevented by a

coup d'état which shifted power from Parliament itself to the Parliamentary New

Model Army, controlled by Oliver Cromwell. The Army had King Charles I executed

and for the next eleven years the British kingdoms operated under military

dictatorship. The Restoration of King Charles II produced a reaction in which the

King regained a large part of the power held by his father; however, Charles'

ministers and supporters in England accepted a substantial role for Parliament

in the government of the kingdoms.

No subsequent British monarch would attempt to rule without Parliament, and after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, political disputes would be resolved through elections and parliamentary manoeuvring, rather than by an appeal to force.

No subsequent British monarch would attempt to rule without Parliament, and after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, political disputes would be resolved through elections and parliamentary manoeuvring, rather than by an appeal to force.

Whigs

The Whigs were a political faction and then a political

party in the parliaments of England, Scotland, Great Britain, Ireland and the United

Kingdom. Between the 1680s and 1850s, they contested power with their rivals,

the Tories. The Whigs' origin lay in constitutional monarchism and opposition

to absolute monarchy. The Whigs played a central role in the Glorious

Revolution of 1688 and were the standing enemies of the Stuart kings and

pretenders, who were Roman Catholic.

The Whigs took full control of the government in 1715 and remained totally dominant until King George III, coming to the throne in 1760, allowed Tories back in. The "Whig Supremacy" (1715–1760) was enabled by the Hanoverian succession of George I in 1714 and the failed Jacobite rising of 1715 by Tory rebels. The Whigs thoroughly purged the Tories from all major positions in government, the army, the Church of England, the legal profession and local offices. The Party's hold on power was so strong and durable, historians call the period from roughly 1714 to 1783 the age of the "Whig Oligarchy". The first great leader of the Whigs was Robert Walpole, who maintained control of the government through the period 1721–1742 and whose protégé Henry Pelham led from 1743 to 1754.

The Whigs took full control of the government in 1715 and remained totally dominant until King George III, coming to the throne in 1760, allowed Tories back in. The "Whig Supremacy" (1715–1760) was enabled by the Hanoverian succession of George I in 1714 and the failed Jacobite rising of 1715 by Tory rebels. The Whigs thoroughly purged the Tories from all major positions in government, the army, the Church of England, the legal profession and local offices. The Party's hold on power was so strong and durable, historians call the period from roughly 1714 to 1783 the age of the "Whig Oligarchy". The first great leader of the Whigs was Robert Walpole, who maintained control of the government through the period 1721–1742 and whose protégé Henry Pelham led from 1743 to 1754.

Both parties began as loose groupings or tendencies,

but became quite formal by 1784 with the ascension of Charles James Fox as the

leader of a reconstituted Whig Party, arrayed against the governing party of

the new Tories under William Pitt the Younger. Both parties were founded on

rich politicians more than on popular votes, and there were elections to the House

of Commons, but a small number of men controlled most of the voters.

The Whig Party slowly evolved during the 18th century.

The Whig tendency supported the great aristocratic families, the Protestant

Hanoverian succession and toleration for nonconformist Protestants (the "dissenters",

such as Presbyterians), while some Tories supported the exiled Stuart royal

family's claim to the throne (Jacobitism) and virtually all Tories supported

the established Church of England and the gentry. Later on, the Whigs drew

support from the emerging industrial interests and wealthy merchants, while the

Tories drew support from the landed interests and the royal family. However, by

the first half of the 19th century the Whig political programme came to encompass

not only the supremacy of parliament over the monarch and support for free

trade, but Catholic emancipation, the abolition of slavery and expansion of the

franchise (suffrage). Whig 19th Century support for Catholic emancipation was a

complete reversal of the party's historic sharply anti-Catholic position at its

late 17th century origin.

GLORIOUS REVOLUTION

GLORIOUS REVOLUTION

The Glorious Revolution, also known

as The Revolution of 1688 and The Bloodless Revolution, took

place in England between 1688 and 1689. It involved the overthrow of the

Catholic King James II, replaced by his daughter Mary II of England, who was

protestant.

CAUSES

When James II became king, removed

protestant officials and people from the army and the church and replaced them

with Catholics. He also suspended unfair laws to Catholics. He tried to

introduce his own laws which were more tolerant of Catholics.

It was thought that these problems would

go away when James died because his daughter, Mary, who was next in line to the

throne, was a Protestant. However, in 1688 James had a son, and the parliament

were afraid that the son could be a Catholic.

Thus, the parliament invited Mary's

husband, William of Orange, who was a prince in the Netherlands, to invade

England and replace James II. William did this and was supported by most

English people so it was an easy victory for him.

DEVELOPMENT

When the son of James II was born, leading

protestants encouraged William of Orange to come to England to investigate the

circumstances of the birth.

William, who was organizing the Grand

Alliance against Louis XIV, needed England as an ally rather than a rival. The

crossing begun on October 19th. William took Exeter and issued a declaration calling for the election

of a free Parliament. From the beginning, the Anglican interest flocked to him.

James II couldn’t do anything to avoid this.

When James marched out of London, there was

even the prospect of battle. But the result was completely unexpected. James

run away to France and followed after them. James he was captured but William

allowed him to escape again. At the end of December, William arrived in London,

ordered the leading peers and bishops to help him keep order, and called

Parliament into being.

CONSEQUENCES

The parliament offered the throne to

William and Mary together but only if they agreed to certain conditions. These

conditions were set out in a document called the Bill of Rights which was

signed by William and Mary in 1689.

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario